UAE’s strategic interests in Libya

Despite the efforts of the international diplomacy, with the Russian-Turkish initiative of Moscow (January 12) and the Berlin Conference (January 19), the cease-fire among the Libyan factions agreed informally in the Russian capital has been repeatedly violated. The artillery gunplay never really stopped, and after the summit in Berlin the clashes surged again, in what seems to be a new escalation.

On January 22 the Kani Brigade, a militia from Tripoli’s hinterland and allied with the leader of the Libyan National Army (LNA) General Khalifa Haftar, resumed to launch rockets against the capital’s only remaining functioning airport of Mitiga. This action was organized and coordinated with LNA, which meanwhile moved forward the capital. In fact, between January 21 and 23, LNA resumed fight in the southern suburbs of Tripoli as well as along the Sirte-Misrata axis.

In these renewed clashes the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Haftar’s most active external backer, played a crucial role. In the two weeks before and after the Berlin Conference, between January 12 and 26, Abu Dhabi airlifted substantial military supplies to the LNA bases in Cyrenaica with almost 40 flights from UAE and Jordan military bases to Bengasi and al-Khadim, using strategic carriers such as Russian-made Antonov and Ilyushin. Logistic efforts like this one are not just a reinforcement of the Haftar positions. They might be preparing a final military push against Tripoli and Misrata forces.

Against this backdrop, Abu Dhabi showed no confidence towards Moscow diplomatic initiative or the process launched by German diplomacy. To understand the reasons for this scepticism, it is necessary to analyze the evolution of UAE approach against the ongoing changes in regional balances.

UAE considers its involvement in Libya as a major chapter in the quest for regional hegemony in which it is opposed to Turkey. Abu Dhabi perceives Ankara as a player willing to exploit the upheavals triggered by the Arab Springs to expand its influence in the region. The prominent instrument of Turkish activism is the support to Islamist parties and movements, in many cases affiliated or close to the Muslim Brotherhood. For decades, in a context of self-referential regimes founded on forms of capillary control of dissent, political Islam has been repressed or marginalized in the region and Turkey embraced it for its apparently “revolutionary” potential. After all, during the 2011 uprisings, Islamism was one of the better-organised platforms supporting the requests of change. In fact, it triumphed in Tunisia, with Ennahda, in Morocco, with the Justice and Development Party, and in Egypt with the Freedom and Justice Party. Ankara trusted in the emergence of these “allied” political forces to multiply its influence in the region. Turkish support to Islamism was designed to favour those parties that could look at Erdogan’s AKP party as a model to imitate, thus recognising Turkey’s hegemony in the region.

This strategy stands in direct opposition on several levels to the agenda of Gulf Monarchies, in particular Saudi Arabia and UAE.

First of all, Abu Dhabi and Riyadh perceive potentially Turkish-backed movements as a possible “fifth column” and a potentially destabilizing internal threat. They fear that Islamist groups in the Arabian Peninsula might be useful to advance the Erdogan’s agenda. Although currently marginal, in fact, these groups could increase their activities in virtual and even real agoras, multiply popular discontent and radicalize social demands. In the next future, this may modify how waves of protest start and evolve, push toward a liberalization of the political arena, and contribute in eroding the ruling families’ legitimacy.

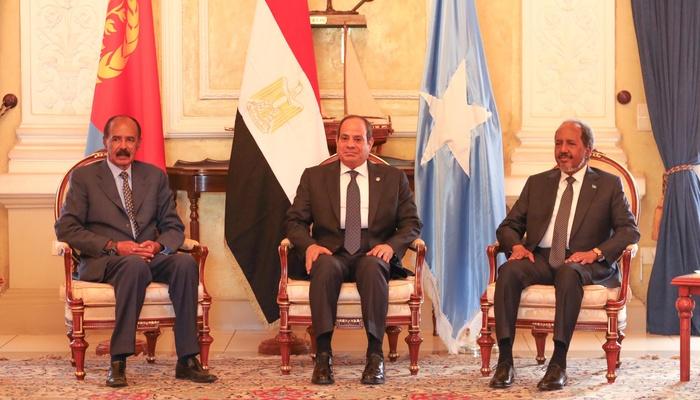

Secondly, promotion of Islamism in the region is seen by Abu Dhabi and Riyadh as the diffusion of an alternative model in competition with the one offered by UAE’s al-Nayans and the Saud family. The latter is based upon the control of the State by an autocratic oligarchy, which guarantees both the internal stability and the selective development of the country’s economic policies. The military oligarchy that has risen to power in Egypt with al-Sisi illustrates this model, which has accurately been replicated in Cyrenaica by Haftar. In Eastern Libya, military élites are the very pillar of this system system, through extensive control of the Military Investment and Public Works Authority.

Besides this structural reason, there are other factors which contribute to increasing the rivalry between UAE and Turkey. Among these, Libya’s role of link between the Mediterranean space and the Sahelian region must certainly be mentioned. Both these regions have been the stage for Abu Dhabi and Ankara activism and competition, in terms of soft power as well as economic penetration. In addition to this, UAE are interested in controlling the port infrastructures in the region (as for Libya, Bengasi and Tobruk). This is a fundamental part of Abu Dhabi’s strategy to become the main regional actor in the maritime trade, while taking advantage of opportunities related to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

In its basic features, the clash between Turkey and the UAE in Libya is strongly affected by ideological polarization. The ideological dimension of the conflict contributes to the rigidity of the two main regional actors’ posture in Libya in an already exacerbated Libyan context where a logic of zero-sum game leaves no space for compromise.

In this sense, from the Emirates point of view, the space for diplomacy in Libya is all the more restricted as Turkish interventionism persists. In 2017-2018, with Turkey distracted by the Syrian dossier and unable to oversee that closely the Libyan one, Abu Dhabi had still attempted to reach a political agreement (with terms robustly favorable to Haftar), showing a genuine commitment to a non-military solution. Conversely, the Turkish intervention in favour of Tripoli’s internationally recognised GNA, which began in May 2019 and intensified with the arrival of Syrian mercenaries and more sophisticated weapon systems last December, contributes to radicalizing UAE’s stance toward a never-ending support for Haftar offensive. Against this background, therefore, Abu Dhabi has perceived the Turkish-Russian initiative in January as an unnecessary provocation (given the central role played by Turkey in the draft agreement), and the Berlin process as an almost anachronistic attempt, disconnected from the situation on the ground and fundamentally incompatible with its strategic objectives.